Three decades ago, while being a young member of the Law and Psychiatry department at Menninger’s, we received a request from local, regional law enforcement to discuss law enforcement in responding to riots. For that presentation, I researched riots from the time of the Civil War to the present. I was aware of the poetic description from Langston Hughes of what happens to dreams deferred. The truth in that final stanza of his poem is felt in the explosive waves of destruction accelerating outward in numerous cities with heart-stopping concussive force. In the historical cyclic nature of riots, that time has again returned.

Several factors contribute to this social unrest suggesting the social therapeutic remedies. In the riots in the ’60s, we found that the political rhetoric inculcated a sense of hope that was frustrated. Our past president ignited an “audacity of hope,” and this country embraced the promise of becoming a more perfect union with equal opportunity for all. The difference in the incarceration and death rates of those of color fueled the Black Lives Matter movement. Further, the economic vulnerabilities to our minority citizens have been in sharper contrast through this pandemic. In an NPR research article published on May 30, 2020, they analyzed the democratic data collected by the COVID Racial Tracker. They concluded based on their analysis nationally that African American deaths occurred at a rate of nearly two times the level that would be expected based on their proportion of the population. In four of the states, the rate was three or four times larger than other groups. In 42 states, Hispanics and Latinos also obtained a higher level of confirmed cases than their percentage of the population. In general Caucasian deaths were lower than for their share of the population in more than 37 states and the District of Columbia. The data set is limited because racial information was only available in 40% of the cases.

The disproportionate health and economic impact of COVID-19 highlights the impact of racial inequality. The CDC outlines the factors that contribute to the higher risk of being infected with COVID-19. Included is the influence of adverse environments. Density is related to the socio-economic level and thus linked to the exposure to the virus. The ability to afford and quickly obtain face masks and other materials that safeguard transmission is also economically influenced. Also, many of our essential workers are racially diverse. Economics affects the food a person eats, their education, possible job flexibility, and access to health care. As a result, those who are disadvantaged economically are more vulnerable in this pandemic.

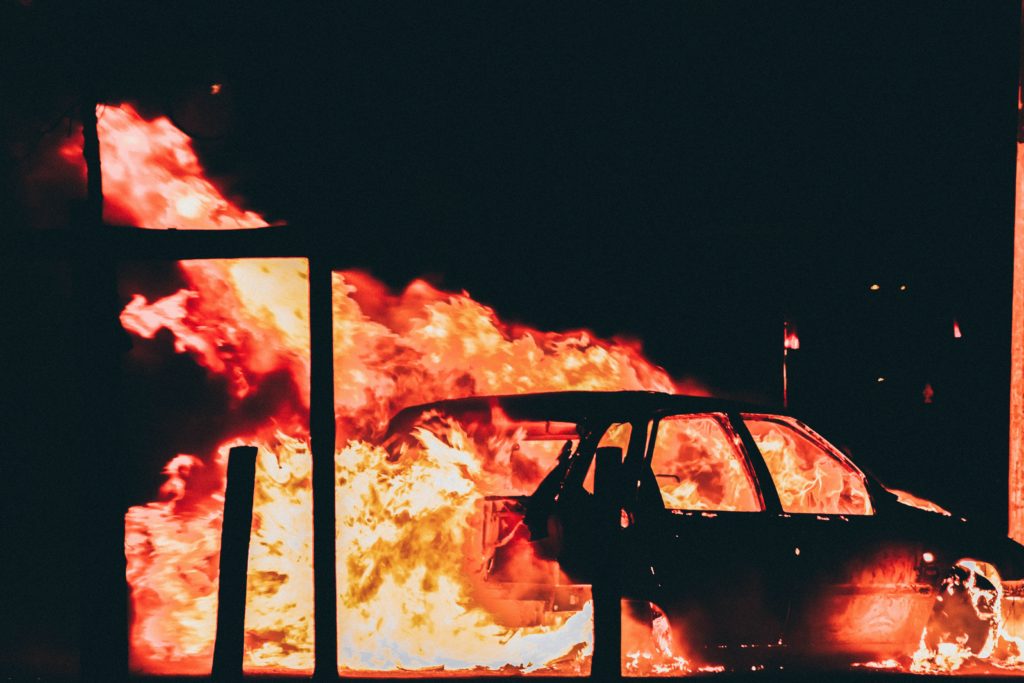

The tinder box of institutional racism is already highly flammable, and the loss of hope for a new era fueled anger. The Supreme Court rolled back civil rights laws seeing them as less needed. However, in minority communities, the sense of discrimination was still palpable. The dream was deferred, and voter registration laws were being changed in the minds of many to disenfranchise minority voters. Added to this was the wrongful deaths of black men and women in the community at the hands of law enforcement, and you have mixed a batch of nitroglycerin.

The death of George Floyd was another match thrown into the tinder box. We have been gradually acknowledging that hurt people hurt other people. Recognizing the impact of trauma, our ability to deliberate its influences on interpersonal relationships have become a foundation for trauma-informed schools and courts. Racism is traumatic and thus responding to hurt with anger only perpetuates cycles of violence. The research on the impact of adverse life events has opened windows to the prevention of interpersonal violence as well as school shootings.

In the book “To Kill a Mockingbird”, a potential lynching of a black man who was wrongfully accused of a crime was stopped in its mounting momentum by the defense attorney’s daughter. She recognized members of the mob and called out their names, restoring the groups dissipated responsibility. Described is an approach to defuse some of the undercurrents fueling mob mentality. The heavy-handed use of force creates an angry mob identity feeding the energy needed for a mob. We have learned from attachment theory and empirically proven couples therapy (EFT) the importance of emotional connections. Watch diffusion of anger in protest. You will soon see a critical change occurs when those who are protesting feel as if they have made a connection on an emotional level. First, those in charge need to come across as accessible. To have the others feel heard, apply active listening skills as an approach. Second, whether kneeling on a knee or joining in the march, the accessible individual must also prove that they are responsive. Finally, they need to demonstrate they are engaged in activities that will lead to understanding and connection, and that they are committed to the changing of patterns of conduct that fuel harm. The way to remember this approach is in the acronym ARE, Accessible, Responsiveness, and Engagement. Our religious communities may help us to connect through a form of community acceptance that enables us to love one another more easily.

At this moment, we may choose to share an optimism grounded in the knowledge that we made it through difficult times before. Further, these protests are drawing a broader cross-section of our population, reflecting a growing consensus that we need to proclaim that Black Lives Matter. We are seeing that responding emotionally and compassionately begins to heal the hurt caused by prejudice. We will eventually move beyond these days and destructive nights by creating an opportunity to dream and shape a new reality inclusive together. With this country’s creativity and concern for each other, we will find unity in our ability to care about each other.

https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html

http://www.napavalley.edu/people/LYanover/Documents/English%20123%20Langston%20Hughes%20Harlem.pdf

http://www.creatingconnections.nl/assets/files/Sue%20Johnson%20ObegiCh16.pdf